On multiple occasions, I've been rightly interrogated about the healthiness and usefulness of low-carb diets by people around me. I've often seen it claimed, that low-carb diets are useless, will make you unhealthy, and don't help you maintain healthy weight.

The claim of such a diet being useless we've already discarded in a prior article, where we unequivocally show, that it can significantly increase survival chances in cancer patients. The claim of unhealthiness, we've attacked in another prior article, where we showed that both saturated fat and cholesterol are associated with lower mortality instead of the often claimed higher mortality. The last claim, that low-carb diets are inherently dangerous to maintenance of healthy weight, we've yet to tackle.

So today, we’ll be looking at two somewhat recent publications, which have to do with the differences in the effect of low-carb and low-fat diets. The main subject of this breakdown is the more recently released publication by Soto-Mota et al. In their publication, Soto-Mota et al. debunk unsubstantiated claims made in a publication by Hall et al. and then move on to reanalyse the data available from the publication of Hall et al..

We’ll discuss the claims of the Hall et al. publication first, and then move to the debunking done through statistical analysis by Soto-Mota et al. before going over the results of the reanalysis done by Soto-Mota et al.

We publish new articles, whenever we've synthesised new findings to a usable degree. You can subscribe to receive articles for free.

Design and Presuppositions of the Hall et al. Publication:

The publication by Hall et al. claims that low-carb diets are worse than low-fat diets at conferring fat loss.

To arrive at this claim they quite reasonably set out to test both diets with every patient. To do this they used a so-called cross-over design, whereby some patients start with one of the two options for x time and then switch over to the other option after x time for another x time.

In this particular study, they did so with a time frame of two weeks, which to me personally sounds too short to achieve proper dietary adaption in the subjects.

Furthermore, Hall et al. used a cross-over design without wash-out, which means, that patients went directly from 2 weeks on one option to 2 weeks on the other option. They did this, because they claimed there existed no carry-over effect, which we’ll go over later, but it basically means they assumed dietary adaption to be instantaneous – a doubtful assertion to be sure.

To summarise the study structure, 20 patients (started with 21, one dropped out) were put each into one of two groups—Group 1 would start with low-carb and end on low-fat, whilst Group 2 would start on low-fat and end on low-carb.

Results of the Hall et al. Publication:

Hall et al. found that mean caloric intake on the low-carb arm was higher than on the low-fat arm, which is as such completely true albeit misleading. Why it’s misleading and what a more nuanced analysis shows, we’ll get into in just a bit.

Verifying/Falsifying the Claim of no Carry-Over Effect:

One of the most important claims of Hall et al. is the claim of there being no carry-over effect. This claim is so essential to verify, because the needed analysis method and interpretation of the results changes wildly with the truth or falseness of this claim.

Soto-Mota et al. sadly didn’t have access to the data of all 20 full-length participants of the Hall et al. publication due to data privacy reasons. As such, they had access to the data of 16 of the full-length participants.

To double check, whether the loss of data from 4 patients would significantly alter the mean data, Soto-Mota et al. prepared baseline characteristics of the original report by Hall et al. and the dataset available to them. They found that there was very little difference in means and data make-up.

We don't take sponsoring or display advertisements in order to keep us free from conflicts of interest. If you've found this valuable, you can help us by supporting our fight against cancer financially.

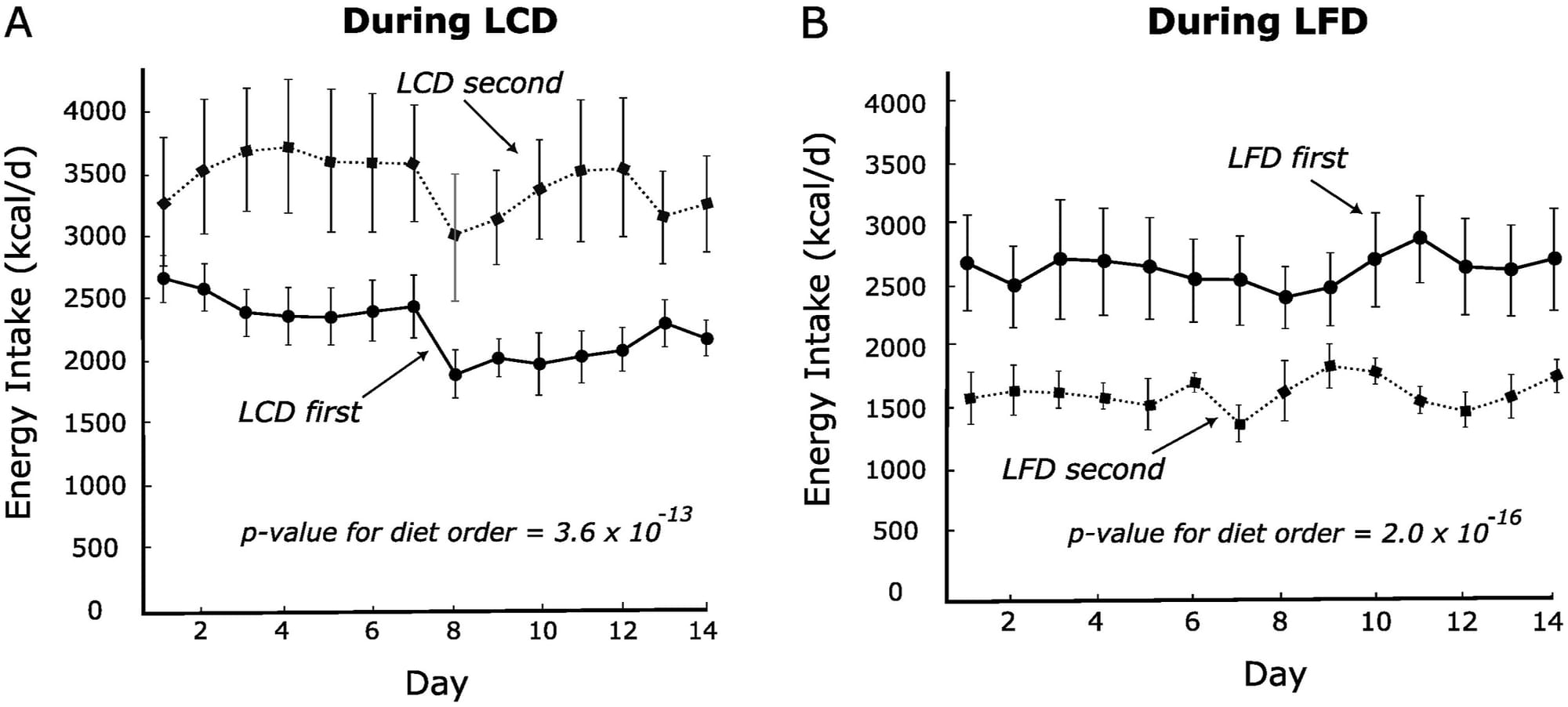

With this out of the way, Soto-Mota et al. looked at the differences in caloric intake in the low-carb arm of both groups. Again, Group 1 started the study off on low-carb and then switched to low-fat, whilst Group 2 started the study off on low-fat and switched to low-carb thereafter.

In doing so, they found that the mean caloric intake was far lower on low-carb diet arms that came first than those that came after a low-fat diet arm. They found the converse for low-fat diet arms. Meaning, low-fat diet arms that came first had higher mean caloric intake than low-fat diet arms that came after low-carb diet arms.

Given the claim made by Hall et al., that there is no carry-over effect, this is highly peculiar, for it unequivocally shows there to be a carry-over effect of some kind. The metabolisms of the subjects are affected from actions outside the respective diet arms. A sort of priming seems to be happening in either diet arm. Low-carb seems to be priming patients to eat less, whilst low-fat seems to be priming patients to eat more as can be seen in the graphic below.

That’s the opposite of what Hall et al. claimed.

So, what does the study by Hall et al. actually show us? Or perhaps the study data rather than the claimed study results?

Reanalysed Result:

To round it all off, Soto-Mota et al. found that the variable of which diet arm came first had a far greater effect upon the mean caloric intake of a patient than did the low-carb vs low-fat diet switch. Which diet arm came first was a thousand times more statistically significant than was the diet arm itself.

This shows that the claimed causality of Hall et al. of the low-fat diet arm being responsible for loss in caloric intake and body fat was incorrect.

Furthermore, it turns the assertion made by Hall et al. on its head.

Looking differentially at the data, the data clearly suggests that low-carb helps with regulating caloric intake and thus fat loss in overweight individuals, and even primes patients to consume less, should they diverge from a low-carb diet for some time after the loss of the low-carb dietary pattern.

The converse is true for the low-fat diet, which helped with increasing caloric intake and thus body fat gain, and even primed patients to consume more calories in general, even when diverging from the low-fat dietary pattern for some time.

Another thing this study suggests, which needs to be tested further is that low-carb diets are better at promoting weight loss than low-fat diets are, but that carbohydrate preloading can indeed increase gorging behaviour on high-fat diets.

Whether this gorging is due to increased fuel partitioning to the adipose tissue due to insulin-priming or due to incomplete coverage of human fat need on a low-fat diet is still unknown. It is in my personal opinion (big mountain of salt) likely to be a combination of both.

In any event, the study design of Hall et al. was clearly ineffectual at testing the hypotheses they set out to differentiate.

To remedy this, a study of similar design could be initiated, with an added wash-out period between cross-overs and longer diet adhesion than 2 weeks.

In any case, I hope you enjoyed this breakdown and will continue to have a great day.

Cheers and God bless.

P.S.: The graph is licenced under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) from Soto-Mota et al. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002231662372806X).

References

Hall, K.D., Guo, J., Courville, A.B. et al. Effect of a plant-based, low-fat diet versus an animal-based, ketogenic diet on ad libitum energy intake. Nat Med 27, 344–353 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01209-1

Soto-Mota, A., Jansen, L.T., Norwitz, N., Pereira, M.A., Ebbeling, C.B., and Ludwig, D.S. (2023). Physiologic Adaptation to Macronutrient Change Distorts Findings from Short Dietary Trials: Reanalysis of a Metabolic Ward Study. The Journal of Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.12.017.